Blog

Hayao Miyazaki: Universally acclaimed weaver of unforgettable anime worlds

This is the 12th in a series on influential figures in the Heisei Era, which began in 1989 and will end when Emperor Akihito abdicates on April 30. In Heisei, Japan was roiled by economic excess and stagnation, as well as a struggle for political and social reform. This series explores those who left their imprint along the way.

He is by far Japan’s most famous animator — in fact, he’s one of the country’s most recognizable living people. Animators and live-action filmmakers around the world acknowledge his influence. His talents have even been described by fans as “godlike.”

But as Japan entered the Heisei Era, which is slated to end with the abdication of Emperor Akihito, Hayao Miyazaki’s upward trajectory was anything but certain.

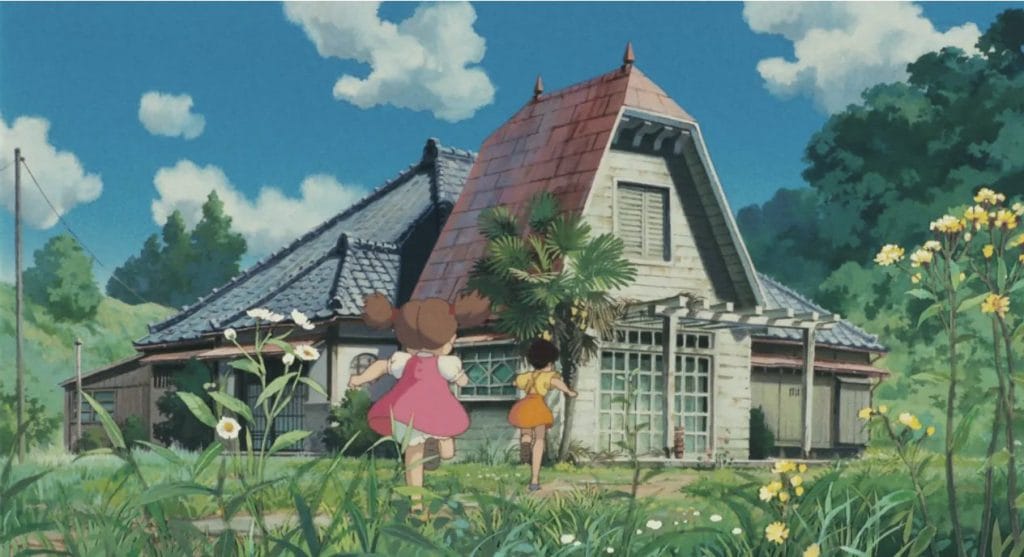

Miyazaki’s last film in the Showa Era had been 1988’s “My Neighbor Totoro.” These days, it’s considered a classic, but the film had underperformed at the box office — as had the director’s previous film, 1986’s “Castle in the Sky.” Without a hit, it was unclear whether Ghibli, the animation studio that Miyazaki had co-founded just a few years earlier, would survive.

But seven months after Emperor Akihito’s ascent, a young woman on a broom swept in to save the day.

“Kiki’s Delivery Service,” Miyazaki’s adaptation of the Eiko Kadono novel about a witch who leaves home for the big city and learns how to be independent, was a massive hit, ultimately becoming Japan’s highest-grossing film of 1989.

Since then, each and every one of the director’s films — including “Princess Mononoke” (1997), “Spirited Away” (2001), “Ponyo” (2008) and “The Wind Rises” (2013) — have seen enormous critical and financial success, transforming Miyazaki into one of the country’s most celebrated directors in any medium, both at home and abroad.

While Miyazaki became one of Japan’s most celebrated figures in the Heisei Era, many of the director’s signature themes came out of his experiences in the Showa Era.

Miyazaki was born in 1941, just months before Japan and the United States went to war. His father and uncle owned a factory that produced parts used in Mitsubishi’s A6M Zero fighter planes, giving the family a relatively high standard of living even as the country began to ration food and other resources.

One incident from this period would have an especially profound impact on the director, says Susan Napier, author of “Miyazakiworld: A Life in Art.” As the Miyazaki family was fleeing the American firebombing of the capital in their car — another sign of their privilege — a mother holding a baby begged to be let on.

“Miyazaki’s father and uncle say, ‘No, we don’t have enough room,’ and drive off,” Napier says. “Miyazaki keeps ruminating about this, saying, ‘I should’ve told my father to stop. Why didn’t I? If such a child were to exist, they could have helped.’”

This incident, Napier says, marked the instant many of Miyazaki’s protagonists — “children who have the moral high ground, children who are mature, thoughtful and highly resilient” — were born.

Napier also singles out Miyazaki’s relationship with his mother during this period as an influence on the strong and complex female characters that populate his films, from Captain Dola in “Castle in the Sky” to Lady Eboshi in “Princess Mononoke.”

“She was a very important force in his life,” says Napier. “She was a very strong character, clearly very smart. She talked politics with Miyazaki, they had huge arguments. … He was seeing a mother, an older woman, not necessarily as someone who was going to take care of you and do the cooking, but as someone you engage with on a very equal level.”

As Miyazaki grew up and entered the animation industry, he met another figure who was to have a huge influence on his life: director Isao Takahata. Takahata, who died in April 2018, imbued Miyazaki with a passion for political activism and environmental issues, and a trip to Sweden the two took together would spark Miyazaki’s long-standing fascination with European landscapes.

The pair would, after the success of the Miyazaki-directed and Takahata-produced “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind,” found Studio Ghibli in 1985. “Nausicaa” was also the first time Miyazaki would work with composer Joe Hisaishi, who has scored all his films since.

Another key figure in the founding of Ghibli was Toshio Suzuki, an editor at the magazine that had financed “Nausicaa.” Suzuki took the reins on the marketing side of the studio, and one of his greatest successes was the 1996 deal in which Disney came to distribute Ghibli films in the United States, exposing Miyazaki to an international audience.

“Miyazaki’s status outside Japan has rocketed since the Disney deal,” explains Helen McCarthy, author of “Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation.” The deal was not without its hiccups, however. When Miramax, owned by Disney at the time, suggested trimming the 134-minute “Princess Mononoke” for its American release, Ghibli sent the studio a samurai sword with a message attached: “No cuts.”

It was the film after “Princess Mononoke” that sealed Miyazaki’s reputation as a master at home and abroad: “Spirited Away,” the story of another resilient child, became the highest-grossing film of all time in Japan — a record it holds to this day — and won the Academy Award for best animated feature. The director, however, chose not to visit the United States to receive the award as a form of political protest, says Napier.

“He was in a really unhappy mood around the time of the Iraq War, particularly angry at Americans leading this coalition against Iraq and bringing Japan into it,” McCarthy says. “Japan’s involvement was very limited but, for Miyazaki, it was very distressing.”

Indeed, Miyazaki has occasionally used his position as the country’s elder animation statesman to wade into political affairs, often publicly railing against attempts to revise the pacifist Constitution.

That said, Miyazaki’s primary influence continues to be on animators, filmmakers and other storytellers.

“I think he’s been influential partly in simply raising Japanese animation into higher estimation around the world,” Napier says. “I think that’s been very influential for young animators, realizing that Japanese animation is admired globally.”

“You’re never going to find ‘Miyazaki Jr.,’” Napier says. “What you’re going to find is another brilliant director who has his or her own vision.”Naturally, those who discover Japanese animation through Miyazaki often search for filmmakers like him, and since he announced his retirement in 2013, the hunt has been on for “the next Miyazaki.”

Such directors have emerged in recent years, in particular Makoto Shinkai (“Your Name.”) and Mamoru Hosoda (“Mirai”), which, McCarthy suspects, may be part of the reason why Miyazaki has decided to come out of retirement.

“He is fiercely competitive,” McCarthy says. “I believe that to see young artists like Shinkai and Hosoda working with a similar aesthetic and reaching new audiences must make him want to show he can still make great movies.”

To what should we attribute Miyazaki’s international appeal over the Heisei Era? Napier credits Miyazaki’s ability to connect with others.

Miyazaki’s next film is set to appear no earlier than 2020, meaning the director’s filmography will run through the reigns of three emperors. And with more people around the world getting their first taste all the time — “My Neighbor Totoro” just received its first official release in China, 30 years after being made — his influence seems only likely to keep growing.

“I think one of the reasons his work is so good is that he’s not looking at things from the outside,” Napier says. “He really is kind of entering into the mind, into the worldview, of very different people: children, young women, older women, animals, spirits. … He has this incredible empathetic imagination.”

McCarthy agrees.

“The emotional tripod at the heart of a classic Miyazaki film is reverence for nature, social responsibility and a determination to keep going,” McCarthy says. “They’re beautifully made, but they mostly have a good, pure and simple heart. I think everyone responds to that.”

Did you know …

Here are five lesser-known works by Hayao Miyazaki:

- “Future Boy Conan” (“Mirai Shonen Conan”) (1978) This 26-episode series, a post-apocalyptic tale centered around an adventurous young boy, served as Miyazaki’s directorial debut. The series was based on the novel “The Incredible Tide” by Alexander Key, but featured major modifications from Miyazaki, who was already showing a strong directorial vision.

- “The Journey of Shuna” (“Shuna no Tabi”) (1983) A one-volume watercolor comic about a prince who sets off on a quest to save his people from famine, “Shuna” shares themes with both “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind” and “Princess Mononoke.” In fact, Shuna’s red elk, Yakkul, will look very familiar to fans of the latter film.

- “Daydream Data Notes” (“Miyazaki Hayao no Zasso Note”) Reprinted several times over the years, this collection contains essays and detailed sketches of planes, tanks and battleships Miyazaki describes as his “psychological release valve.” Despite his staunch anti-war stance, the director’s well-documented obsession with war vehicles came to a zenith with his 2013 film “The Wind Rises.”

- “On Your Mark” (1995) This sci-fi short — the music video for the single of the same name by rock duo Chage & Aska — contains many of Miyazaki’s signature themes, including concern for the environment. Initially pulled from a Ghibli Blu-ray box following Aska’s drug-related arrest, it was, to the relief of many Miyazaki fans, later restored to the collection.

- “Boro the Caterpillar” (“Kemushi no Boro”) (2018) Miyazaki’s latest film, this Ghibli Museum-exclusive short was computer animated, a first for the director. The trials and tribulations of its creation are the subject of the recent documentary “Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki.”