‘Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man’: 15 years as Studio Ghibli’s bridge to the world

There’s a lot to be learned from living with the Never-Ending Man. That’s Hayao Miyazaki, the renowned director of animated films such as “Spirited Away” and co-founder of the celebrated animation house Studio Ghibli. The nickname was coined by an NHK documentary about his penchant for retiring and unretiring again and again.

Miyazaki’s former housemate and the author of “Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man” is Connecticut-native Steve Alpert who, for 15 years, was a senior executive at Studio Ghibli and headed up its international division. The book chronicles Alpert’s job as Ghibli’s bridge to the wider world, which involved everything from negotiating distribution deals to serving as Ghibli’s representative at the 2003 Academy Awards where “Spirited Away” won the award for best animated feature.

“Working with the people at Ghibli, and other incredibly talented people during the making of the foreign language versions of its films, it occurred to me that, hang on, I should be writing some of this down,” says Alpert from his home in New Haven, Connecticut, where he has lived since leaving Ghibli in 2012.

Originally published in Japanese in 2016, the book largely takes place in the late ’90s and early 2000s, a comparative Wild West when it came to the licensing and localization of Japanese animation abroad.

“You could do things then that you wouldn’t be able to do now,” says Alpert. “Way back then I could just call up (former Pixar producer and director) John Lasseter because of his relationship with Miyazaki, and he would sit with me for an hour or two to give me advice on how to get Ghibli films distributed in North America.”

“Never-Ending Man” offers a look into how, with Alpert’s help, Ghibli forged a distribution deal with Disney — and how that fragile deal took a few beatings from egotistical producers (on both sides), inevitable cultural clashes and even threats by the now-disgraced Harvey Weinstein to cut 30 minutes from Miyazaki’s “Princess Mononoke.”

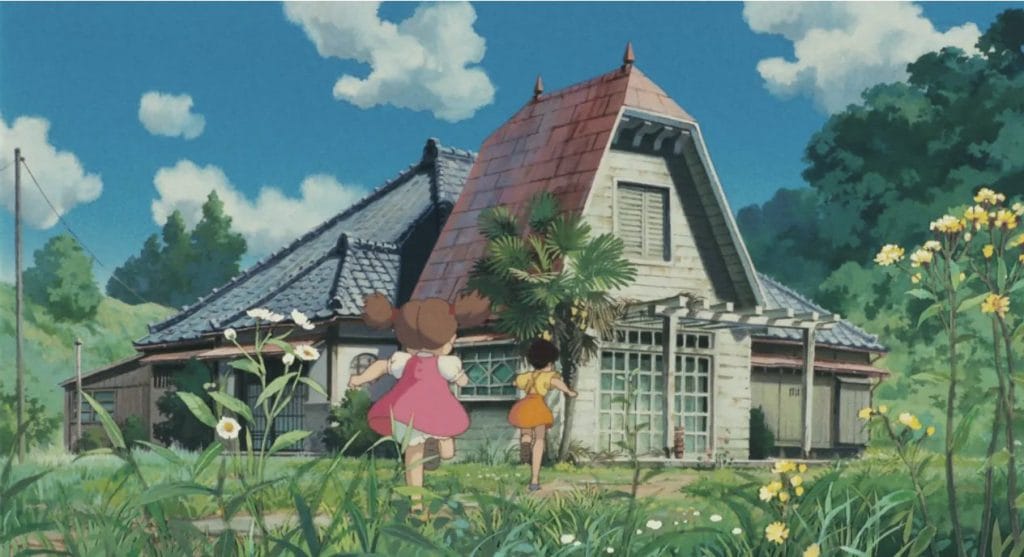

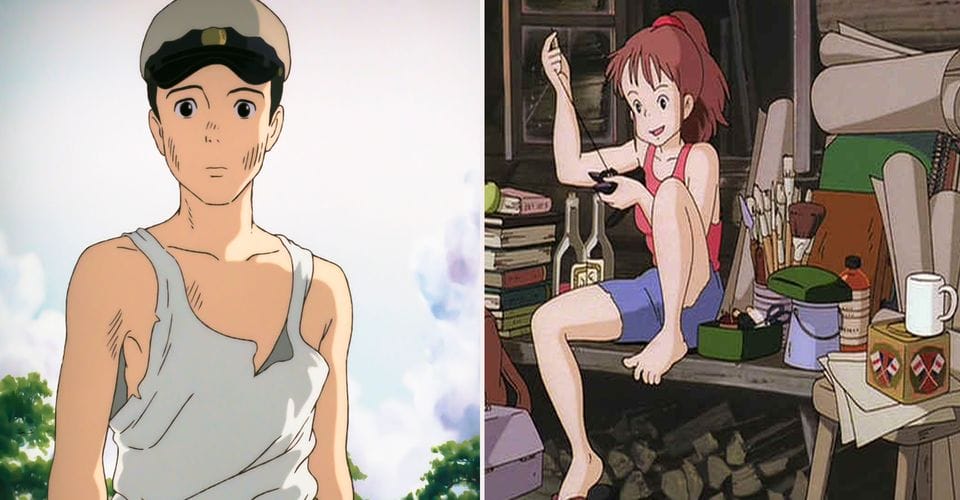

Ostensibly, the main focus of the book is the Never-Ending Man of the title, and Alpert shares memorable stories of his time spent with Miyazaki, including journeys to Europe where the director found himself fascinated by the architecture and decidedly less so by the cuisine. (Fed up with Michelin-starred French restaurants, Miyazaki led Alpert on a hunt for a Japanese restaurant in the middle of Paris.) And Miyazaki is clearly fond of Alpert: He even modeled the German character Castorp in “The Wind Rises” after him and had him voice the role.

But as head of the studio’s distribution arm, Alpert spent far more time in the company of Toshio Suzuki, the producer in charge of all Ghibli’s business-related decisions.

“(Suzuki) spent a lot of time in his car and I was very fortunate to be riding along with him for some of it, overhearing his speakerphone conversations and being offered his wisdom and his stories. He also spent a lot of time making me understand the business of animated filmmaking,” says Alpert.

Aside from the wisdom of uber-producer Suzuki, Alpert also profiles Yasuyoshi Tokuma, the founder of Tokuma Shoten, the publishing company that financed Ghibli’s films. Alpert describes Tokuma, in his 70s at the time, as “your grandfather on steroids,” and devotes a large chunk of the book to the larger-than-life boss, describing his fast friendships with politicians and yakuza alike, and even his star-studded funeral in 2000.

“To me he represents another era in the cultural history of Japan. For all his quirks and I suppose even what could be called his faults, to me he represented the passing of an era.”

If in many ways Studio Ghibli is a company without peer, it is in other ways quintessentially Japanese. Alpert’s wry recollections of his time at the studio beget a larger take on Japanese business culture — and how non-Japanese (sometimes awkwardly) fit into the mix.

“What it’s like to be a gaijin (foreigner) working in Japan is mainly what the book is about,” says Alpert, and many of his trials and travails will ring true to anyone who’s spent time here — though not all of us have negotiated video distribution deals with shady Taiwanese businessmen or nearly lost film festival trophies in airports.

Despite leaving Ghibli and Japan, Alpert has been keeping a close eye on the Never-Ending Man, who announced his retirement in 2013 but was back to work on a new feature-length film soon thereafter. (According to Alpert’s old boss Suzuki, 36 minutes of that film are complete as of May 2020.)

“Despite the press conferences and everything, I never really believed that Hayao Miyazaki would retire,” says Alpert. “I think it’s apparent that he still has quite a lot to show anyone who cares about the art of animation. His amazing imagination is certainly still intact.”