Review | Ghibli’s ‘The Wind Rises’ is Dream-Like and Thought-Provoking

Studio Ghibli‘s anime swan song is a visually stunning, and emotionally devastating, examination of ambition and priorities.

The Wind Rises conjures some interesting questions about the moral responsibilities of art, and with any luck inspires heavier investigation into the man whose life it chronicles. But in borrowing inspiration from a man who wanted nothing more than to make something beautiful, Hayao Miyazaki accomplishes the same goal as his subject, crafting a biography of Japanese engineer Jiro Hoshikoshi that is wonderfully poetic and evocative – if also potentially neglectful of the larger context, and the repercussions, of creating something that is used for destruction.

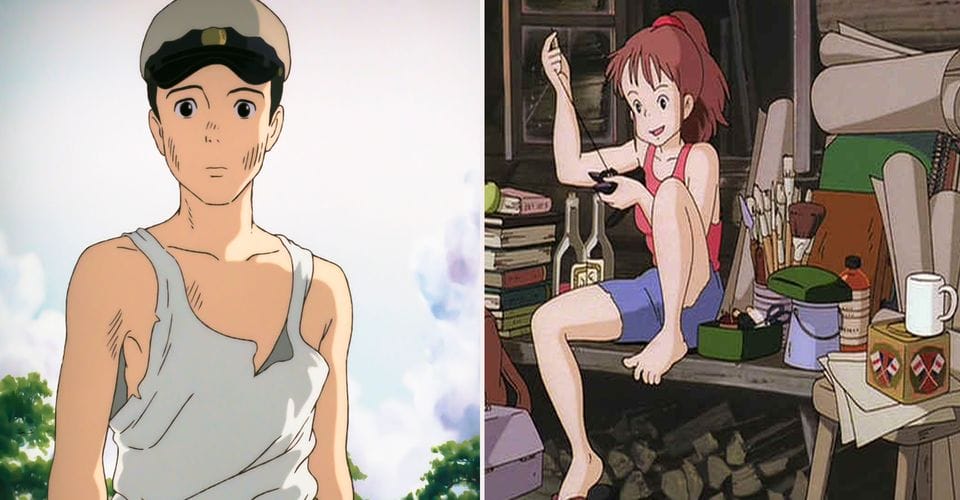

An English-language dub of the film stars Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Horikoshi, a spirited and optimistic young man with a lifelong dream to build airplanes. Inspired by dream-conversations with Italian plane engineer Giovanni Caproni (Stanley Tucci), Horikoshi graduates from the University of Tokyo with honors and lands a job designing planes for the government. But when several of the prototypes designed by him and his best friend Honjo (John Krasinski) fail, Jiro is sent on a sabbatical to find the inspiration that will produce the best plane Japan has ever produced.

While on a retreat at a summer resort, Jiro reconnects with Naoko (Emily Blunt), a woman he altruistically helped when they were much younger, and they soon fall in love. But after discovering she’s receiving treatment for tuberculosis, which is incurable, Jiro finds his attention divided between his lifelong passion for aviation and his newfound one for Naoko.

The film’s opening sequence simultaneously throws down a gauntlet and issues a mission statement of sorts: Jiro, lost in his dreams, soars through the skies alongside great, fantastical flying machines, eventually getting “shot down” and crashing to Earth. Anyone familiar with Miyazaki’s work will undoubtedly recognize the surrealism of the scene, but it both highlights Jiro’s creative preoccupations and suggests that this will not be a conventional biography, or even one bound by fact. That Miyazaki makes this choice feels almost like a test to ensure the audience is prepared, and eager for the kind of story he plans to tell.

Interestingly, stories like Jiro’s are fairly commonplace as a cinematic formula – characters, usually men, driven to a kind of achievement or excellence despite adversity or opposition. But where The Wind Rises differs is that, primarily, it is based on real events, even if its interpretation of many of those events is heavily fictionalized. Consequently, it’s more difficult than in perhaps purely fictionalized circumstances to separate the larger ramifications of that ambition – in this case, the fact that no matter Jiro’s stance on aviation engineering, he was expressly helping design airplanes that would be used for war.

It’s an important question in two ways: one, how that knowledge affected Jiro’s enthusiasm or passion for engineering, and two, whether it’s responsible for the film to ignore that detail in Jiro’s life. Or perhaps more directly, are we responsible for the uses applied to the things we create? The film doesn’t ever address this, and as gorgeous and emotional as the story is, the absence of that exploration is always felt.

That said, the film’s pairing of Jiro’s personal goals with his romantic involvement with Naoko provides a poignant counterpoint to that notion of following one’s vision at all costs. Naoko is sort of ceaselessly understanding of his commitment to his work – a possibly accurate portrayal given the cultural mores of the time – but any humanistic interpretation of the story suggests that he makes the wrong choice by focusing on his work rather than the woman he loves. And even if the movie doesn’t quite make explicit the trade-off he must eventually accept, the juxtaposition makes a powerful case for questioning what things are truly most meaningful to us when we set our priorities.

On a pure aesthetic level, meanwhile, the film unfolds like a dream – deeply vivid and convincing, without approaching anything as banal as realism. As each propeller of the various planes in the film starts spinning, for example, you can hear the sound of voice actors doing their best childlike impersonations of machinery. An earthquake that destroys Tokyo in one of the early scenes combines proper foley work and more voice acting, to make the whole experience more intimate, and in a strange way, more pure. Notwithstanding those moral quandaries, Miyazaki truly captures the romanticism of creation, and the sense of fulfillment that comes from truly earned achievement.

Ultimately, it’s up to each viewer to find the answers, and determine the significance of the questions the film conjures. But as a story of a man’s life, and his creative ambitions, Miyazaki’s latest – and by all accounts, possibly his last – is a truly stunning, emotionally devastating experience. And perhaps in ironic contrast to the absence of that more unflattering consideration, what The Wind Rises does best is highlight how great inventions and incredible creations can be perverted when people know what best to do with them – and if nothing else, exert a cost to their discoverers as personally devastating as the impact of their misuse upon the world.