How Studio Ghibli’s Tales From Earthsea Fails Ursula K. Le Guin’s Classic

Goro Miyazaki’s failure to adapt the source material well makes the Tales From Earthsea even more disappointing.

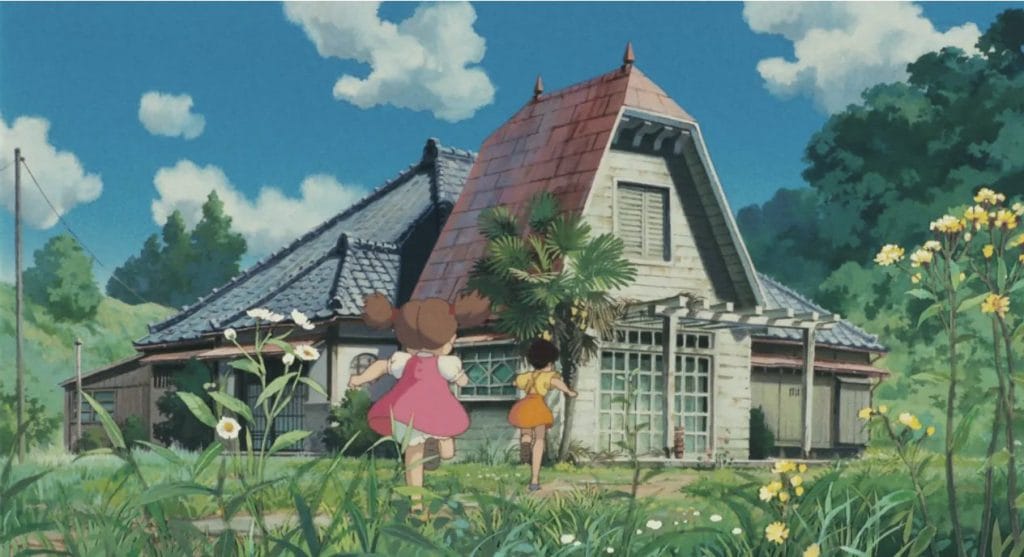

Tales from Earthsea is commonly regarded as one of the weakest Studio Ghibli films. Goro Miyazaki’s 2006 directorial debut isn’t necessarily an awful movie, but when contrasted to both the rest of the Ghibli library, and the highly regarded source material, it’s rather dull.

What makes it worse is that author Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Earthsea Cycle appears perfectly suited for a Ghibli adaptation. The fantasy epic — six books, published between 1968 and 2001 — deals with themes common to other Ghibli films, from the balance of nature to how no people are truly evil but rather seek out selfish ends through unwise methods. The failure to adapt the source material well makes the film horribly disappointing.

The Majesty Of Earthsea

Le Guin’s The Earthsea Cycle consists of five novels and a collection of short fiction. Each story is brief, but covers a unique journey dealing with, or tangibly connected to, the life of a legendary wizard named Ged, from his adolescent years to his mastery of (and ultimate sacrifice of) magical power and knowledge. Each book deals with high-seas adventure across an empire spread over an archipelago.

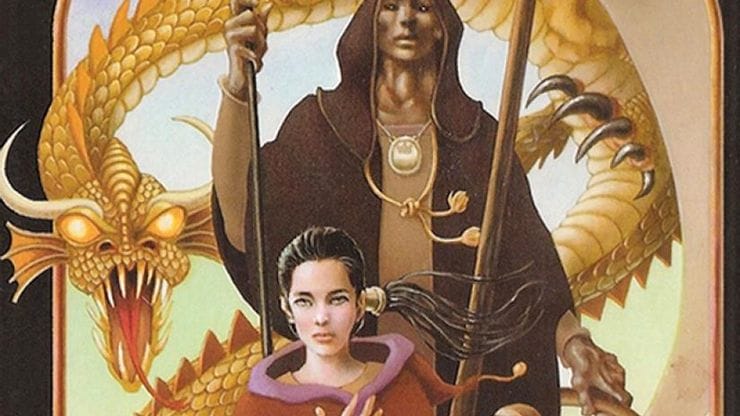

The first novel, A Wizard of Earthsea, was published in 1968, three years after Frank Herbert’s Dune and 13 years after J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. However, what set Earthsea apart was its racially diverse cast of characters, and its focus on internalized conflict.

In the first novel, Ged (more commonly called Sparrowhawk) confronts a shadow of his own creation that chases him across Earthsea, representing his own reckless pursuit of power without care of the consequences. In the second novel, The Tombs of Atuan, the main character Tenar has to unlearn the toxic teachings of an underground cult worshiping a Lovecraftian entity of terror and dread, all while Ged tries to sponge the toxicity of the titular tombs from Earthsea, both literally and figuratively.

Lost In Adaptation

These plots both play into Goro Miyazaki’s Tales from Earthsea. However, if you hadn’t read the books, you’d never recognize the significance of the Shadow person or why Tenar expresses fear when in the dark. You wouldn’t even know why Sparrowhawk is such a significant figure in the story at all. That’s because Tales from Earthsea is an adaptation of the first four books of The Earthsea Cycle, primarily adapting the third and fourth books: The Farthest Shore and Tehanu. These books take place around the same time, but their plots do not significantly intersect.

Aside from failing to recapture the spirit or plot of the original series, the film only really adapts two components from each book: there’s a bad guy named Cob who wants to stop death and there’s a dragon disguised as a girl named Tehanu — sometimes referred to as Therru. The character arcs of all the characters are flattened. The scarred Therru’s arc in the book deals with sexism and bigotry, themes that aren’t present in the film. Cob as a villain remains underdeveloped. While the books go in-depth about his fear of death and how he represents what Ged could have been if he’d never sacrificed his selfish pursuits, Cob here is just a creepy weirdo who doesn’t want to die.

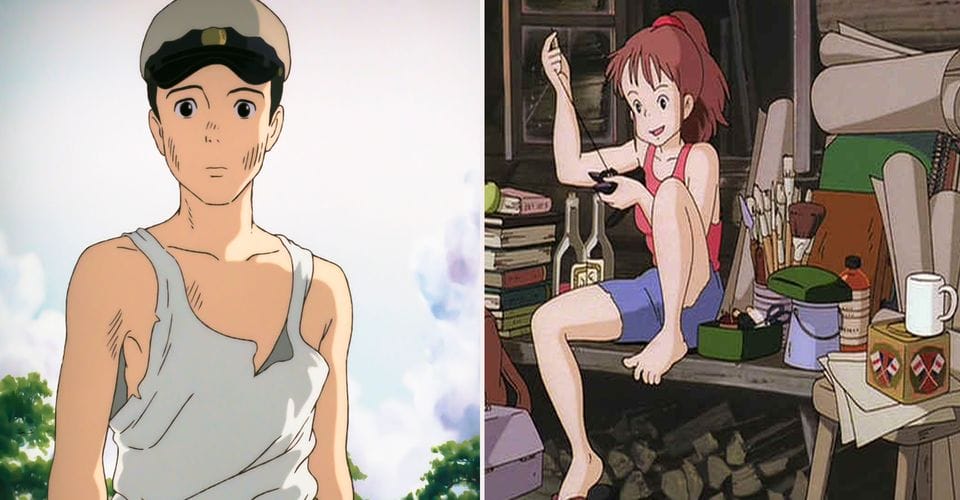

The film fails to show who Ged or Tenar actually are as people, despite them being the two central characters. They have no character development, aside from possibly Prince Arren’s arc to accept responsibility for his actions. The character who is most horribly flattened is Tenar, who goes from a bone-chilling, blood-thirsty cultist on the path to redemption to just a friendly farmer lady taking care of a few kids.

Soulless Worlds

The world of Earthsea in the film lacks dimension. The complex magic system of memorizing the true names of the world and all the applications of magic in society is greatly simplified. The characters seldom if ever acknowledge they’re living on a series of islands. The role the ocean plays in their lives is minimized. While dragons do appear, the film rarely explains how dragon society functions or why Therru can disguise herself as a human.

The most visibly apparent issue — and one that Ursula K Le Guin most explicitly criticized — is how the darker skinned characters who made up the majority of the book’s cast were given pale skin. In an accurate adaptation, Ged should have red skin, Arren should be brown-skinned and the only White character in the cast should be Tenar.

All of these problems result in Earthsea becoming a lifeless, dull place. The characters do not feel alive, but worse than that, the world itself does not feel alive. All of this leaves Tales from Earthsea feeling like a pale shadow of the series’ true self.